Descripción de datos

Los datos utilizados en este estudio provienen de la encuesta MASZK.29,30, un gran esfuerzo de recopilación de datos sobre patrones de mezcla social realizado durante la pandemia de COVID-19. Se llevó a cabo en Hungría desde abril de 2020 hasta julio de 2022 con periodicidad mensual. Los datos se recopilaron mediante encuestas telefónicas representativas, anónimas y transversales utilizando la metodología de entrevista telefónica asistida por computadora (CATI) e involucraron una muestra grande representativa a nivel nacional de 1000 cada mes. Durante la recopilación de datos, no se pidió a los participantes información que pudiera usarse para su reidentificación. La recopilación de datos de la encuesta telefónica se llevó a cabo después del consentimiento informado del encuestado al comienzo de cada entrevista. Cualquier información sobre los niños se obtuvo haciendo preguntas a sus padres o tutores legales después del consentimiento. No se recogieron datos de la encuesta de ningún sujeto menor de edad. La recopilación de datos cumplió plenamente con las normas de privacidad de datos europeas y húngaras vigentes y fue aprobada por la Autoridad Nacional Húngara para la Protección de Datos y la Libertad de Información.47 y también por el Comité de Ética Científica y en Investigación del Consejo de Ciencias de la Salud (resolución número IV/3073-1/2021/EKU).

El objetivo principal del esfuerzo de recopilación de datos fue seguir cómo las personas cambiaron sus patrones de contacto social durante los diferentes períodos de intervención de la pandemia. Relevante para este estudio, los cuestionarios registraron información sobre la contactos sociales proxydefinido como interacciones en las que el encuestado y un compañero permanecieron a menos de 2 m durante más de 15 minutos48, al menos uno de ellos sin máscara. Se registraron números de contacto aproximados entre los encuestados y sus pares de diferentes grupos de edad de 0 a 4, 5 a 14, 15 a 29, 30 a 44, 45 a 59, 60 a 69, 70 a 79 y mayores de 80 años. De los cuales agregamos los dos últimos grupos en 70+. Los datos del número de contactos sobre niños menores de edad se recopilaron pidiendo a los tutores legales que estimaran los patrones de contacto diarios.

Más allá de la información sobre los contactos antes y durante la pandemia, el conjunto de datos de MASZK nos proporcionó un amplio conjunto de información sobre características sociodemográficas (género, nivel educativo, and so forth.), condiciones de salud (enfermedades crónicas y agudas, and so forth.), situación financiera y laboral (ingresos, situación laboral, oficina en casa, and so forth.), y actitud hacia las medidas y recomendaciones relacionadas con COVID-19 (actitud hacia la vacunación, uso de mascarillas, and so forth.) de los participantes. Para estudiar las diferentes etapas de la pandemia, consideramos seis períodos epidemiológicos, incluidas tres ondas epidémicas (W) y tres períodos intermedios (IP) (ver Fig. 1a).

Sobre los datos recopilados, la empresa de investigación de encuestas elaboró e implementó un procedimiento de muestreo probabilístico de múltiples pasos, estratificado proporcionalmente, utilizando una base de datos que contenía números de teléfonos fijos y móviles. La tasa de respuesta a la encuesta fue del 49%, cifra notablemente superior a la tasa de respuesta media (entre el 15% y el 20%) de las encuestas telefónicas en Hungría. La muestra es representativa de la población húngara de 18 años o más por sexo, edad, educación y domicilio. Para corregir los sesgos de muestreo, utilizamos ponderación particular person para disminuir la diferencia entre la distribución de la población y la muestra de las variables sociodemográficas. Las ponderaciones fueron calculadas por la empresa de investigación de encuestas responsable de la recopilación de datos. Para el cálculo de los pesos se utilizó rastrillado.49que se basa en un ajuste proporcional iterativo50. Se pueden encontrar más detalles sobre el procedimiento de ponderación en la Sección 1.3 de SI. Después de la recopilación de datos, solo los datos anonimizados y cifrados se compartieron con las personas involucradas en el proyecto después de firmar acuerdos de confidencialidad.

Dimensiones sociodemográficas

Las dimensiones sociodemográficas que analizamos son las siguientes: (i) Nivel de Educación, que puede tener cuatro niveles posibles: bajo, medio-bajo, medio-alto y alto; (ii) situacion laboral, que pueden ser empleados o no empleados, incluidos estudiantes y jubilados; (iii) ingreso percibido (llamado simplemente ingreso a través del manuscrito) puede tener tres niveles posibles: bajo, medio y alto; (v) género se refiere al género biológico y puede ser femenino o masculino; (v) asentamiento, que se refiere al área donde viven las personas y puede ser capital, rural o urbana; (vi) enfermedad crónica es una dimensión booleana que indica si un individuo está afectado por alguna enfermedad crónica; (vii) enfermedad aguda es una dimensión booleana que indica si un individuo está afectado por alguna enfermedad aguda, y (viii) fumar es una dimensión booleana que indica si un individuo es fumador o no. Una explicación detallada de estas variables se proporciona en la Sección 1.1 del SI.

Datos atractivos

Todos los análisis sobre el número de contactos se han realizado tras haber eliminado los valores atípicos en el percentil 98% respecto al periodo de interés. Todos los resultados presentados en este trabajo han sido calculados contabilizando a cada participante según su peso representativo, como se detalla en la Sección 1.3 de SI. Además, para evaluar la incertidumbre de la estimación de contactos y matrices de contactos, empleamos la técnica de muestreo bootstrapping, como se describe en la Sección 3 de SI.

análisis estadístico

Para construir un modelo epidemiológico que tenga en cuenta explícitamente las desigualdades sociales, necesitamos identificar cuáles son las principales dimensiones que interactúan con la edad y afectan más los patrones de contacto. Para identificar estas dimensiones, modelamos el número esperado de contactos del encuestado. i usando una regresión binomial negativa18,51 como se outline en la ecuación. (1):

$${mu }_{i}=alpha+{beta }_{1}{{{{{{rm{edad}}}}}}}}_{{{{{{{ rm{grupo}}}}}}}}_{i}+{beta }_{2}{X}_{i}+{beta }_{3}{{{{{{{ rm{edad}}}}}}}_{{{{{{{{rm{grupo}}}}}}}}_{i} * {X}_{i}+{epsilon }_{i},$$

(1)

donde grupo_edadi es la clase de edad de i; Xi es la variable de interés (p. ej., educación, ingresos, and so forth.), grupo_edadi ({*}) Xi es el término de interacción del grupo de edad y la variable de interés, y ϵi es el término de error. Dado µidefinimos ({lambda }_{i}=exp ({mu }_{i})) ser el número esperado de contactos para el encuestado i. Luego modelamos el número reportado de contactos para el encuestado. i, yicomo

$${y}_{i} sim ,{{mbox{Neg-Bin}}},({lambda }_{i},, phi ),$$

(2)

dónde ϕ ∈ [1, ∞) is a shape parameter that is inversely related to over-dispersion: the higher ϕ is estimated to be, the closest yi’s distribution is to a Poisson distribution with rate parameter λi.

We build model (1) for each variable of interest (X). Particularly, the interaction term between age_groupi and the variable of interest allows us to examine whether there are differences in the effect of Xi on the number of contacts in the different age groups. To be able to provide a meaningful description of the interactions, we analyse the average marginal effect (AME)52,53,54 of Xi on the number of contacts for different age groups, defined as

$${{{{{{{{rm{AME}}}}}}}}}_{{X}_{i}}= frac{1}{n}{sum }_{i=1}^{n}frac{partial {mu }_{i}}{partial {{{{{{{{rm{age}}}}}}}}_{{{{{{{rm{group}}}}}}}}}_{i}} frac{partial {mu }_{i}}{partial {{{{{{{{rm{age}}}}}}}}_{{{{{{{rm{group}}}}}}}}}_{i}}= {beta }_{1}+{beta }_{3}{X}_{i}.$$

(3)

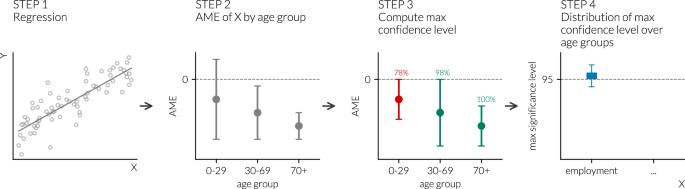

Working with categorical variables (e.g., education level or employment situation), we can calculate different AMEs for all categories of the categorical variables in each age_group. It means, that, for example, for the interaction of the settlement type (with three categories, out of which one is a reference category) and age (with five categories) on the number of contacts, we have 2 × 5 = 10 different AME values: one for each settlement category by each age category. However, as we would like to know the overall effect of the interaction with the given variable, settlement, we have to aggregate these values into one measure. Therefore, we developed the following strategy. For each age group, we examined all the AMEs related to the category of the variable analysed (e.g., all AMEs related to the categories of the settlement type). In each case, we calculated the confidence level55 at which the confidence interval belonging to the AME of a given category reaches zero. The higher this calculated confidence level is, the more certain we can be that the given variable category has an effect on the number of contacts in the given age group. Equivalently, the estimated effect is significantly different from zero at a smaller type I error probability. Out of these confidence levels, we consider the maximum confidence level for each age group as that denotes the highest confidence level at which the AME of the given variable (e.g., settlement type) reaches zero, i.e. the smallest type I error probability33 at which the estimated effect is significant. Finally, to summarise the results across age groups, we look at its distribution. By following this procedure for each of the variables of interest in the different waves of the pandemic, we are able to rank the variables according to their importance in driving differences in contact patterns additionally to age, in different periods of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pipeline of these analyses is illustrated in Fig. 6.

Following the same methodology, we investigate the dimensions that, in interaction with age, affect the most the probability of getting vaccinated against COVID-19. In this case, we model this probability using a logistic regression model instead of a negative binomial, as the dependent variable was binary and not a count one (see Section 2.2 of SI for further details). Although the data were aggregated to obtain NPIs-homogeneous periods, minor variations in restrictions persist within certain intervals (see SI Fig. 3). Thus, acknowledging the importance of NPIs in shaping human contact during the COVID-19 pandemic, we tested the validity of our results when considering this effect. Additionally, we account for the interplay of vaccination behaviour and contacts, which can be significant in dynamic situations when vaccination strategies are implemented during an epidemic crisis56. Specifically, we have included two additional control variables in the statistical model (1): (i) the Oxford Stringency Index, a composite measure quantifying the government’s response strictness to the pandemic, and (ii) a dummy variable indicating individual vaccination status (vaxi). The results of these robustness analyses are presented in Section 2.1.2 of the SI, along with further robustness analysis where we control for all the other available individual features. Additionally, we investigate the effects of NPIs on vaccination uptake, with results presented in Section 2.2.1 of the SI. All the results of the robustness analysis align with those discussed earlier and lead to the same qualitative conclusions.

Decoupled contact matrices

Conventionally, to compute age-contact matrices Cij we divide a population into subgroups according to their age and calculate the average number of contacts that individuals in age class i have with individuals in age class j30. Here, instead, we further stratify individuals from each age class i according to various dimensions, like employment status, settlement or education level.

In detail, we decouple the conventional age contact matrix Cij into D number of matrices, one for each of the subgroups of the dimension that we want to take into account. More precisely, let (bar{d}) be the subgroup of the dimension considered and let (bar{d} in 1,ldots,D). We can write

$${C}_{bar{d}i,, j}=C{T}_{bar{d}i,, j}/{N}_{bar{d}i},$$

(4)

where (C{T}_{bar{d}i,j}) is the total number of contacts that individuals of age class i and belonging to subgroup (bar{d}) have with individuals in age class j, regardless of the subgroup to which the contacted individuals belong; and ({N}_{bar{d}i}) is the total number of individuals in age class i and subgroup (bar{d}).

For example, to differentiate between employed and not-employed individuals, we compute two age contact matrices: Cemployed,i,j and Cnot-employed,i,j. All these matrices have been corrected for symmetrization as explained in Section 4.3.1 of SI. This framework can be extended to any number of dimensions considered simultaneously, in this case, the length of the (bar{d}) vector will correspond to the number of combinations of the levels of the dimensions considered. Note that the available data lack information on the subgroup membership of contacts, recording only the demographic details of survey respondents. Consequently, we opted to decouple the age contact matrices solely along the dimension of the respondent.

The epidemiological model

In order to investigate the effect of the decoupled contact matrices on the dynamic of infectious disease transmission, we propose a simple mathematical framework as an extension of the conventional age-structured SEIRD compartmental model34,35.

The conventional SEIRD model is defined as a population where individuals are assigned to five compartments based on their actual state: susceptible (S), exposed (E), infected (I), recovered (R) and dead (D). The model further defines the transition rates of individuals from one compartment to another by incorporating for each age class a given force of infection, which includes the average number of contacts with all the other age classes. The model proposed here extends this definition by taking into account not only the age structure of the contacts in the population but also their differences along a set of other dimensions (bar{d}), such as education level, income level and employment situation.

The model can be described by a set of ordinary coupled differential equations as presented in Eq. (5):

$${dot{S}}_{bar{d},i}, =, -{lambda }_{bar{d},i}{S}_{bar{d},i} {dot{E}}_{bar{d},i}, =, {lambda }_{bar{d},i}{S}_{bar{d},i}-epsilon {E}_{bar{d},i} {dot{I}}_{bar{d},i}, =, epsilon {E}_{bar{d},i}-mu {I}_{bar{d},i} {dot{R}}_{bar{d},i}, =, mu (1-{{{{{{{rm{IF{R}}}}}}}_{{{{{rm{i}}}}}}}}){I}_{bar{d},i} {dot{D}}_{bar{d},i}, =, mu {{{{{{{rm{IF{R}}}}}}}_{{{{{rm{i}}}}}}}}{I}_{bar{d},i}.$$

(5)

Here i indicates the age group of the ego, j indicates the age group of the peer, (bar{d}) represents a vector of dimensions to which the ego belongs, β is the probability of transmission given a contact, ϵ is the rate at which individuals become infectious, μ is the recovery rate, IFR is the infection fatality rate, and ({C}_{bar{d}}) is the age contact matrix corresponding to dimensions (bar{d}).

In this system of equations system, we rely on the concept of the force of infection, which is defined as

$${lambda }_{bar{d},i}

(6)

Further, we rely on the definition of the infection fatality rate (IFRi), which is defined as the fraction of infected individuals that died. In order to account for the variability of contacts in our data, for each simulation that we run we use a static decoupled contact matrix that we compute from a bootstrapped sample of our data. See Section 7 of SI for the details on the implementation of the numerical simulations.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.